“One student replaces three specialists” – and today?

- cmessina53

- 19. Mai

- 3 Min. Lesezeit

Aktualisiert: 27. Mai

Twenty years ago, the Reutlinger General-Anzeiger published an article about my thesis project. The headline read: “One student replaces three specialists.”

The project involved developing a fully automated laser cutting system for miniature springs made of hardened CuBe – a material thinner than a sheet of paper, delivered in coiled helix form. Tiny orientation holes were meant to guide the cutting process. That was the theory.

In practice, the challenges were significant:

the material was extremely fragile

feeding the parts was problematic

positioning accuracy wasn’t reliable enough

the laser cut was on the edge of technical feasibility

and communication between the subsystems was still immature.

Several engineers had already spent more than a year trying to crack the problem. No one seriously believed it could be solved any time soon – least of all by a fresh graduate with no industry experience. I mostly received sympathetic smiles rather than actual trust.

Well – perhaps they underestimated me.

At 14, I started experimenting with AMOS and Blitz Basic on my Amiga 500 – and I never stopped coding after that. (Yes, I also played Monkey Island, Bundesliga Manager, Shadow of the Beast and Defender of the Crown.)

At 16, I was working as a student in production at Federn Vogt in Reutlingen, measuring automotive components stamped by 400-ton Schuler presses running compound tools. One stroke every two seconds – a sound you don’t forget.

At 17, I worked at Ruwel in Pfullingen, producing multilayer circuit boards. I went through every department – etching, coating, tinning, drilling, printing – and got to experience all of it up close. 500-degree molten tin occasionally splashing out of the bath – a thrill for young and old.

As a student assistant at Bosch in Reutlingen, I operated second-generation SMD pick-and-place machines, already equipped with visual inspection systems. They watched the assembly process, and I watched them – industrial espionage of the friendly kind.

Maybe I wasn’t quite as green as one might assume of a mechanical engineering graduate. After all, I had also learned the basics of countless hands-on skills around the house, in the garden, and on cars, growing up alongside my father.

So yes, I figured it could be done: a Trumpf laser, a Mitsubishi controller, a smart Cognex camera, the necessary mechanics for feeding and ejecting parts, and a few piezo motors to position the product – all combined into a mechatronic “clockwork.”

A bit of youthful naivety didn’t hurt, either.

The result was convincing: a tiny component measuring 10.50 mm in length, cleanly separated between two 0.35 mm punched holes – later integrated into a new blood pressure monitor, documented in patent US2016367156A1.

And today?

It raises the question whether experiences like this will even matter in the future, given the pace of AI development. Or if they still make a difference at all.

The world today is a very different place than it was back then. And most of us wouldn’t have been able to predict how, or how fast, it would change. Few people still tinker with their cars. Many of the companies I worked for no longer exist. And code? Today, a language model writes it for you, with varying degrees of quality.

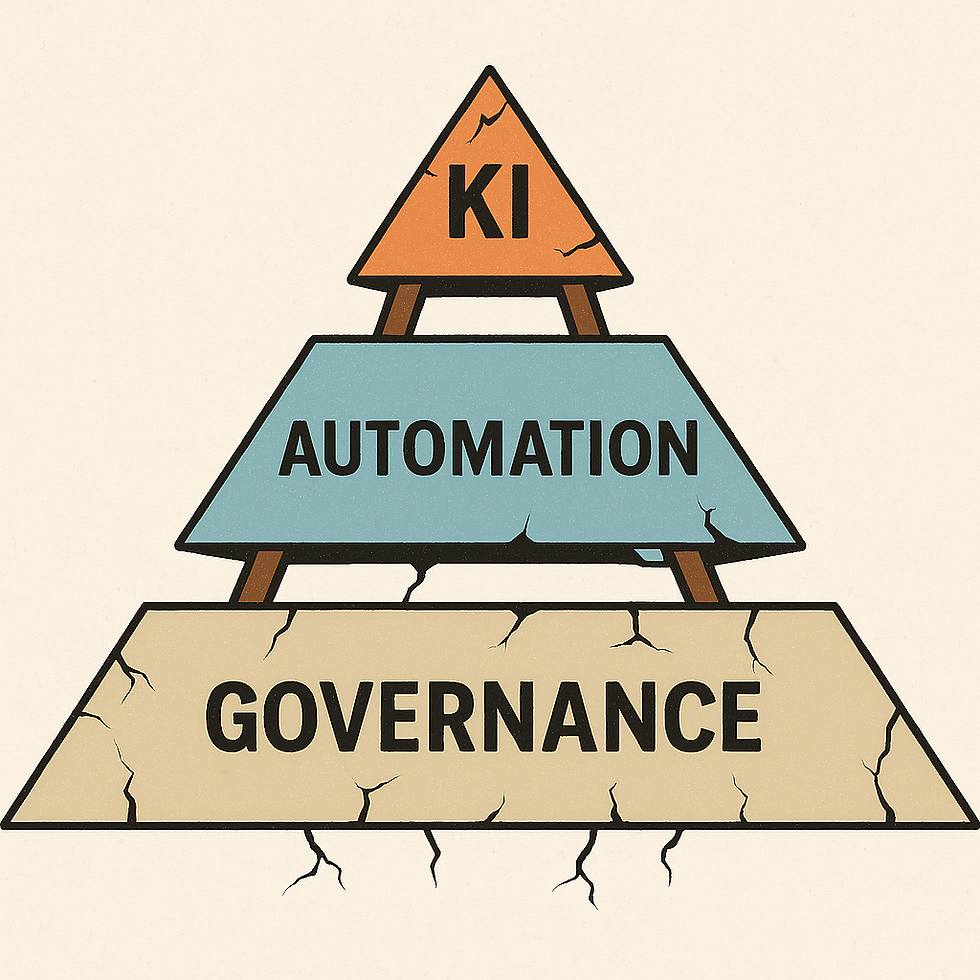

So: if experience can be embedded into AI – does it mean human experience becomes irrelevant? Should we stop building it ourselves and just rely on what machines “learn”?

This could be the most difficult question for all our engineers to come.

Of course, we should welcome these tools. Use them. Learn from them. But not at the cost of our own curiosity, our own craftsmanship, our own ability to adapt and question. If you stop learning and engaging, you risk waking up one day to find you’re no longer in control – but being controlled.

So what should we do?

Stay calm. Keep learning. And most importantly: go out. Touch things. Feel problems. Make mistakes. Take responsibility. Don’t just simulate – experience. Because nothing replaces experience – not even the smartest algorithm.

That’s what I want my son to understand. That’s why I gave him a fret saw for Christmas – and a programmable robot for his birthday.

So here’s my advice to anyone just starting out:

Don’t just rely on the next prompt. Don’t get stuck behind GPT. Seek what AI cannot give you: the real world, real people, real accountability.

The rest will follow.

And by the way – thanks to Mark Reich, who years later managed to get me the original digital print plates from that GEA article. A thoughtful gesture, no agenda – simply because he could.

I doubt a mechanical colleague with a chip in its head would have understood that moment.

Kommentare